Sorry, we just couldn't resist quoting the Godfather of soul in the title of todays blog! But as epic as those funk chords strummed by Catfish Collins in James Brown's Sex Machine may be, we're actually focusing on electric guitar construction rather than playing this week. Yup, it's all about the bridge.

Diving straight in

Actually, 'dive-bombing straight in' might be more appropriate. Because one of the coolest sounds an electric guitar can make, and definitely one of the techniques that always catches the imagination of rookie guitar players, is using the whammy bar for immediate and extreme pitch alteration. It certainly blew my young mind when I first encountered a video of Joe Satriani and Steve Vai duetting - both players occasionally grabbing that weird stick thing poking out of the front of their respective signature model Ibanez's, and expertly sending the frequency south or north with effortless distorted flair. Words can't describe JUST how much I wanted to try that particular stunt, and the frustration that my own budget Les Paul copy wouldn't allow me to even try it!

This early exasperation has now mellowed over the past 20 years, along with my occasional ownership of nearly as many electric guitars during that time, fitted with a variety of bridges and vibrato systems. So, for any new players reading this article, wondering if the string anchoring system on their own instrument is 'right' or 'wrong', and maybe curious about whether different bridges would better suit their style, let me cast a light on this fascinating subject.

Saddle up

What is a guitar bridge anyway? Well it kinda serves multiple purposes - anchoring the strings to the body end of the guitar, aligning them correctly in terms of height over the fretboard (aka the 'action' of the guitar), and assisting in carrying the strings vibrations through the guitar body.

It's here that we can kick off with a huge plus for electric guitarists. Pretty much ALL electric guitar bridges feature an easily adjustable 'saddle' - the first solid point that strings pass over at the body end of your guitar, marking one end of their total vibrating length. This simple adjustability usually covers both string height and intonation, irrespective of whether your guitar features a whammy bar. And it's fantastically simpler than having to carry out the physical alterations required when fine-tuning acoustic guitar saddles.

So, taking it as read that painless recalibration is generally built-in to most electric guitar bridges, what are your options?

Fixed

This description covers the most basic and reliable methods of holding strings onto a guitar body, with (usually) no real mechanical complexity involved. And for those of you with no interest in whammy bars, there are various tried and tested designs out there, including...

Hardtails: As simple as it gets. An all-in-one block, where strings are fed through either the rear of the bridge or from the back of the guitar body, and straight over the saddles. The Fender Telecaster is probably the best example of this bridge design in action – it’s remained essentially unchanged for around 70 years!

Wraparound: Also super-simple, albeit fairly rarely seen these days. A simple adjustable saddle mounted on a substantial metal bar, with the strings attached to the back and then 'wrapping around' the whole ensemble. Generally associated with early (and now hugely valuable) Gibson instruments, until they replaced it with...

Tune-o-matic: Gibson's trademark two-piece bridge, and standard equipment on the Les Paul. Strings are anchored through a chunky metal 'tailpiece' attached to the front of the guitar body, and then run over a separate adjustable tune-o-matic saddle.

Tailpiece bridges: This description basically covers just about every other low-tech fixed bridge design not already mentioned. Strings pass through a tailpiece attached to the bottom end of the guitar (usually anchored near the strap button), then over an adjustable saddle. Stylish and classic - think Rickenbacker, Gretsch, most of the big-bodied Gibson’s, and basically just about every other semi-acoustic electric guitar of note.

Vibrato

First-off, let's address the elephant in the room. A TREMOLO ARM IS NOT REALLY A TREMOLO ARM!!!!

The 'tremolo' effect refers to a variation in amplitude, whereas the 'whammy bar' attached to many electric guitars in fact allows the player to temporarily alter the pitch of the strings - an effect actually called 'vibrato'. But ever since the late, great Leo Fender mistakenly referred to the system on his iconic 1954 Stratocaster as a "Tremolo Device For Stringed Instruments", this erroneous description seems to have endured. Not that Fender was incapable of producing products that could indeed carry off excellent tremolo effects - his superb Vibrolux guitar amp of 1956 for example. #Facepalm.

But if you DO want a whammy bar, what are the options? Let's first consider systems that you can fit to the front of your guitar, such as..

Bigsby: The original and possibly most attractive vibrato system ever, patented by Paul Bigsby in 1952. A beautifully curved, spring-loaded arm that rotates a cylindrical bar in the tailpiece to vary tension in the strings BEFORE they run over the saddle. Infamously less reliable than most other vibrato systems from a 'keeping the damn thing in tune' perspective, but still hugely popular with rock'n'roll players.

Stetsbar: Substantially less common or well-known as the Bigsby system, but just as interesting in appearance. These devices were originally designed for Gibsons, but have been manufactured to retro-fit just about every popular model of electric guitar with minimal modification required. Definitely to be considered a boutique item, but lauded by fans for reliability and versatility.

Now for the two most copied ideas in whammy-bar history...

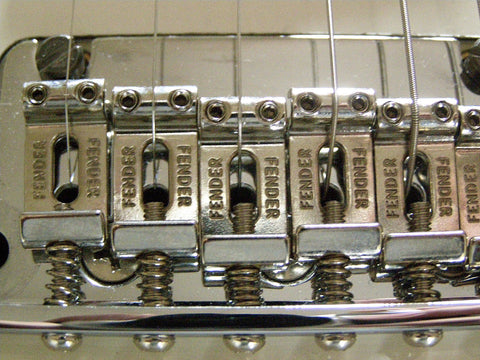

Synchronised tremolo: Leo Fenders contribution to the history of guitar vibrato systems, without which rock music would certainly have sounded very different, and standard equipment on the Stratocaster since – well, forever! It’s basically a one-piece unit, consisting of a chunky block of metal that sits within the guitar body (through which strings are fed from the back of the instrument), attached to a front-plate that holds the saddles and arm. The front-plate is loosely attached to the guitar body, allowing the entire fixture to pivot, with heavy springs located in the guitar body to counter-act the string tension and hold the whole unit in place. The result? Hugely reliable for staying in tune, very effective in use (especially for drops in pitch), and at least as simple as a hardtail when performing string changes. Which is why it remains the most copied design in guitar vibrato history.

Locking/floating tremolo: Any number of models fall into this category, but the classic example remains the Floyd Rose. Whether or not you believe the rumours that Eddie Van Halen was involved with the design, his use of this system was a huge contributing factor in its popularity and credibility. A locking plate on the headstock nut fixes the strings in place after initial tuning (ensuring stability, and explaining the 'locking' description), with fine tuners for each string located on the bridge itself. This is a sort of all-in-one tailpiece/saddle to which the strings attach - one end of which literally 'floats' above the body cavity where the springs are located. These springs are precisely balanced against the tension of the tuned strings, which allows a huge amount of leeway when pulling/pushing the whammy bar - insane highs and even madder lows are easily achieved, to a much greater extent than basically any other type of vibrato construction.

Sounds almost too good to be true? There is one major downside - the balancing act between string tension and spring tension has to be exact, meaning that any string breakages (or even changes in basic string gauge) instantly plunge the instrument action into an unplayably high or low state. Professional guitar technicians find these beasts annoying enough to work on, never mind a rookie trying to sort out their instruments at home!

Wrapping it up

And there you have it - an introduction to the weird and wonderful world of electric guitar bridges. There's certainly many more options out there for players than just the mainstream designs we've discussed here (the recent 'Evertune' fixed design that literally refuses to go out of tune is certainly well worth a look!), but we've covered enough ground to hopefully give our rookie readers an idea of what sort of tantalizing tailpiece technology might suit them best.

So, until next time...

...peace out!

1 comment